Blog

Julian Lavoto: Kewa Silversmith

December 03 2019

1 Comment

1 Comment

Julian Lovato, born in 1922, was born on the Santo Domingo (Kewa) Pueblo. Both Lovato’s parents were expert heishi bead makers and jewelers, he learned the traditional Kewa techniques as a young man from them. After his time in the military he took his education to the next level, working under tutelage of famed Italian silversmith Frank Patania Sr., apprenticing at the Thunderbird Shop in Santa Fe. During his time there, he honed his skills of working with silver and gold and he quickly became one of the master pueblo craftsman of the 20th century.

His jewelry is best known for the high quality of turquoise and coral he selected for each piece. This quality and his exceptional silversmithing made Lovato a renowned artist. He merged his traditional designs with the modern esthetic favored by Patania Sr., blending it into what Lovato called "raised, dimensional jewelry design". Lovato eventually moved on and opened his own shop, but continued to use the Patania Studio thunderbird hallmark even after he left.

Lovato passed away in 2018, his body of work has placed him in the top tier of Native silversmiths of the 20th Century including the likes of Mark Chee, Charles Loloma, Joseph Quintana, and Kenneth Begay.

We currently have a ring made by Julian Lovato available for purchase.

Biography: Col. George Alexander Forsyth

March 12 2019

Colonel George Alexander Forsyth (Born November 7, 1837-Muncy, PA; Deceased September 12, 1915 –Rockport, MA)

George A. Forsyth was not your typical military man. He attended Canandaigua Academy in New York and studied law at the Chicago Law Institute, which led to an apprenticeship with Attorney Isaac N. Arnold, a close friend of Abraham Lincoln. His first foray into war was enlisting with the Chicago Dragoons, serving as a private, shortly after the Civil War began.

His first commission came in September 1861 as a first lieutenant in the 8th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry. During his time with the 8th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry, he participated in many battles and campaigns, which quickly moved him up in rank, beginning with the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia in 1862, which advanced him to Captain in February of that year. He ended as a Brevet Brigadier General (March 1865) and was aid to Major General Philip Sheridan who commanded the Division of Missouri. He accompanied Sheridan on his famous ride at the Battle of Winchester and forged a strong bond with the Major General during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign (1864-1865).

Forsyth became a member of the regular US army in 1866; he was place on frontier duty in the West. He continued to rise over the next two years to become major of the 9th US Calvary. In 1886, Major General Sheridan agreed to and drafted orders to allow Forsyth to hand pick a force of 50 frontiersmen and scouts who were well versed in the surrounding terrain and the ways of Indian Warfare. He would lead this force most often against the Cheyenne in Colorado, Kansas, and Nebraska. All though the men were organized similarly to a company of cavalry, they were not officially soldiers, rather employees of the Army.

The battle that Forsyth is most known for is the Battle of Beecher Island. The battle took place along, and eventually in, the Arikaree River. It lasted for a total of 9 days, beginning September 16th, 1868. During the battle, Forsyth and his men were driven on to a small sandy island (later named Beecher Island) and warded off repeat attacks from three converging bands of Cheyenne, Sioux and Arapaho warriors. During the assault, Forsyth was wounded in two different incidents.

The Battle of Beecher Island earned him a brevet to brigadier general. He then served as Military Secretary from 1869-1873. This role included tasks such as helping to restoring order after Chicago’s Great Fire of 1871; organizing a buffalo hunt for the Russian Grand Duke Alexis; and heading military missions to Japan, China, India, and Europe. He continued he military career into the 1880s, including serving as the lieutenant colonel of the 4th Calvary during the Apache Wars.

By the end of the 1880s, Forsyth’s military career was coming to a close; most notably for the court-martial he faced July 1888. He was formally retired for medical reasons March 25th 1890.

He turned to writing after the end of his military career, writing “A Frontier Fight” for Harpers magazine, The Story of a Solider and Thrilling Days of Army Life. In 1904, his rank was up’d to the rank of colonel on the retired list.

We received a unique pipe bag from Forsyth's collection. The beaded bag was passed down in his family along with several photographs and copies of the books that he wrote, including one that has his personal bookplate inside. To learn more about this unusual pipe bag click here

Reference Material used: The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607-1890: A Political, Social and Military History, edited by Spencer C. Tucker.

Artist: Gary Minaker-Russ

December 04 2017

Gary Minaker-Russ (born 1958) is one of the foremost contemporary First Nations carvers of argillite at present. His carving is not only characterized by traditional form and content, but also with traditional techniques, like leaving his carvings with a tool-finished matte black-grey surface. He is best known for his work with argillite, but has also worked in other mediums including silver casting, wood, and soapstone. He is a carver of poles, sculptures, boxes, bowls, and jewelry

Each piece Gary carves is an original design, His distinct carving style exhibit a profound understanding of sculptural form and his imaginative and powerful interpretations of the ancient Haida legends show his sensitivity to the importance of subject matter.

Gary is from the Eagle Clan of Masset, Haida Gwaii. Gary studied under his brother, Ed Russ, and sister-in-law, Faye Russ at the age of 14. learning the stories, forms and techniques essential to his craft. Gary's career as a carver began to take shape in 1977. By 1980, he devoted himself full time to carving, quitting his jobs as a logger and fisherman

His work has been exhibited worldwide in galleries, museums and private collections, most notably at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, Quebec, and the Royal British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria, BC. In 2008, Gary was one of fourteen argillite carvers featured in Carol Sheehan’s book Breathing Stone:Contemporary Haida Argillite Sculpture.

We currently have one piece by Gary Minaker-Russ. To learn more about The Haida Eagle Head Carving click on the image below.

.

Artist: Frank Patania Sr.

October 05 2017

2 Comments

2 Comments

Frank Patania Sr. was born in Messina Italy in 1899. At the age of 6, he began an apprenticeship in goldsmithing. Frank was taught that he would have to master each task given to him before he could move forward in his training beginning with the sweeping of the floor, learning two valuable lessons: “first, a master’s understanding of every aspect of the craft. And second, the discipline to put that understanding to work.”

Patania Sr. was on his way to New York City at the age of 10. He would reside with his family in New York from 1909 to 1924. During his time in the city it was difficult for him to find work in his field as the newly installed child labor laws limited many of his options. He had to attend school to learn English and in turn was able to start work as a machinist, due in part to the need for metal working in the war efforts of WWI. After the war ended he was able find work as a jewelry designer for Stern & Company at the age of 19. Here, he would obtain a great understanding of then-current trends.

In 1924, Patania Sr. contracted tuberculosis. Out of concern for how serious the disease was Stern & Co., would send their talented designer to Santa Fe, New Mexico to recover. This journey to the Southwest would mark a big change in direction of Patania’s designs and the medium in which he worked.

In 1927, Patania Sr. opened his first Thunderbird shop in Shelby. It was in the perfect location, only steps away from the railway ticket office. This put him in a prime location to sell his pieces to the tourists that were flooding the west by train and Indian Detour cars.

The business grew in 1930 to include Pantina Sr.’s wife Aurora Masocco who helped manage the store and became a conceptual designer in her own right, creating fabulous designs. It became even more of a family affair after Pataina’s brother and sister-in-law also joined the business. They expanded to feature Indian pottery and copperwork.

Ever the hard worker, Patania Sr. dedicated himself to learning all he could about Native American jewelry. In earlier years he was trying to find his artistic voice in the new mediums. His work was of high quality and feature many hallmarks of the Southwest Navajo jewelry. By 1937, his hard work and eye for detail led to the opening of a second shop, located in Tucson Arizona.

Into the 40s and 50s his eye for spotting trends and implementing them into his work, led Pantania Sr. to incorporate naturalistic elements into his pieces, which instantly became a big hit. His ability to incorporate trends and execute popular styles in turquoise and sterling silver led him to many patrons form the local art scene like Mable Dodge and Georgia O’Keeffe. This success led him to hire Native American Craftsman. They assisted him in creating his pieces and helped to provid enough inventory to satisfy both shops and a booming mail order business. In 1950 He would open a third shop in Tucson.

During a return trip to Italy in the 1950s Patania Sr. would obtain a beautiful collection of coral that would invigorate his designs once again. He continued to work, staying on top of trends and producing pieces that would forever label him the “Cellini of the Southwest”. In 1964 Frank Patania Sr. lost his battle with cancer.

Many early pieces from the shop are unsigned, then the shop proceeded to add a thunderbird to its pieces and further still an embossed conjoined “FP”. The most recognizable mark is an incised conjoined “FP” with the Thunderbird mark.

You can see many of Frank Patania Sr.’s pieces in museums across the country, including the Smithsonian.

We Currently Have four pieces by Frank Patania Sr and the Thunderbird Shop. To learn more about one of our items for sale, click on the item's image below.

To learn more about Frank Patania Sr:

Video: Arizona Public Media did a feature on the whole Patania Family and the Thunderbird Shop. Click here to watch the video

Books: The Patanias: A legacy in silver and gold by Joanne Stuhr

Resources used

Patania: 70 years of Excellence by Shari Watson Miller featured in Modern Silver Magazine

"About Patania Jewelry: Frank Patania Sr." by Sam Patania

"A History of the Patania and Thunderbird Shop Hallmarks" by Frank Patania Jr.

Hopi Silversmithing: The development of Hopi Silverwork and the Hallmark Overlay Technique in Hopi Jewelry

June 30 2017

Beginning in1930 there was an increased interest in Hopi crafts, especially Hopi silverwork, through the encouragement of members of the Flagstaff Art community, namely Dr. Harold S. Colton, Mary Russell Ferrell Colton (founders of the Museum of Northern Arizona), and Virgil Hubert (Assistant Art Curator at MNA). Helping to further the exposure of Hopi Crafts was the establishment of the Hopi Craftsman Exhibit presented by the Museum of Northern Arizona in 1939. The event gave Hopi tribal members a place to sell their wares and encouraged them to hone their skills. The Hopi silversmiths were encouraged to make jewelry that was uniquely Hopi, instead of making copies of Navajo or Zuni Designs. Mrs. Colton enlisted the help of Mr. Hubert to create designs for the jewelry pieces, derived from Hopi pottery, basketry, and textiles as a way to assist the silversmiths in the design process. However, due to the United States entering WWII in 1941 the making of crafts and more specifically silverwork stalled. There were shortages of raw materials, as well as the expectation that every able-bodied man would participate in the war effort, at home and abroad.

The summer after the war ended in 1946 was a time of reinvigoration for the Hopi Art community. Fred Kabotie along with other Hopi Villagers were able to pull together enough crafts and silverwork to have a small exhibition at the Snake Dance held in Shungopavi. In attendance was Dr. Willard Beatty, a member of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board and then Director of Education for the BIA. Shortly after the event, Dr. Beatty met with Fred Kabotie and Paul Saufkie to propose a GI training program that would provide courses in silversmithing to the returning Hopi Veterans, while also providing a source of income to them to help support their families.

In February of 1947, Fed Kabotie and Paul Saufkie began teaching classes with the mindset of of making a true statement with Hopi jewelry. Fred Kabotie, a well- known artist in his own right would teach design and Paul Saufkie, master silversmith, would teach silverworking techniques. The 18-month program was set to assist 15 Hopi veterans gain a new profession. They would use the designs originally created by Virgil Hulbert during the Hopi Silver Project and a book of Mimbres Pottery designs prepared by Fred Kabotie to inspire their own personal designs.

The classes were not easy. Each jewelry design had to be approved by Kabotie before the newly trained smith could begin working on it. It took time to find the right combination of designs that would speak of the Hopi culture. Once approved the men would hammer bars of silver into sheets and begin the process of creating their jewelry. Over the course of the program the Overlay technique was developed. It began with the concept of appliquéd silver that was used in Virgil Hubert’s designs. What was originally considered leftover scraps would become the foundation for the Overlay technique.

The Overlay technique is when two pieces of silver are soldered together after a design has been cut from the top layer, creating a negative design. Most silversmiths would create metal templates of their designs, which would allow them to trace a design onto the sheet of metal. The designs would then be cut out using a tiny saw blade. The templates could be used over and over and mixed together to create unique jewelry pieces. The artist would then add texture to the area of the bottom layer of silver that was visible. The final phase of construction, involved the visible areas of the bottom layer to be oxidized or blackened with a chemical agent, which allowed the top design to stand out.

This technique helped fuel the design process. By July 1949 there were enough pieces created that the silversmiths could participate in the Hopi Craftsman Exhibit.

After the first cycle of veterans graduated from the program, the Hopi Silvercraft Cooperative Guild was formed, which allowed the men who had entered the program to continue working after the program ended and they would no longer be receiving substance payments. The guild was able to obtain a loan for $5,000.00 to continue making jewelry. After the second class graduated the facility used for the classes was used full time by the guild.

In 1962, a large facility was constructed and to this day pieces are still sold there by local Hopi Silversmiths.

Featured Artist: Douglas Holmes, member of the Badger Clan. He was a member of the first class of Veterans to take part in Fred Kabotie and Paul Saufkie’s classes. He actively made jewelry from 1948 to 1961. His mark is that of a Butterfly with outstretched wings.

take part in Fred Kabotie and Paul Saufkie’s classes. He actively made jewelry from 1948 to 1961. His mark is that of a Butterfly with outstretched wings.

If you would like to learn more: Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing by Margaret Nickelson Wright

.

Artist: Josef Presser

May 29 2017

Josef Presser, born April 18, 1909 in Lublin, Poland immigrated to Boston, MA in 1913 and at the age of 12 was admitted into the Boston Museum School of Art on a four-year scholarship. Being the youngest student ever admitted to the program indicated how much talent he already possessed.

After completing his program at BMFA, Presser returned to Europe to work and study art abroad in the late 1920s. There he studied the works of the Renaissance masters as well as gain inspiration for future work by becoming employed by circuses and other traveling shows. Much of his work from this time shows his interest in horses.

He returned to the United States in 1931 to pursue his painting career in Philadelphia, PA. Here, he would begin his career painting murals for the WPA, as well as accepting private commissions for horse portraits and murals. He also began to sell his paintings that had a greater level of intensity that reflected the seriousness of the Great Depression.

In the mid 1930s Presser moved to New York, NY, and met Agnes Hart, a NYC artist and his future wife. After his marriage to Agnes Hart, he would move to a studio on 14th St in New York, NY (1940) and a year later added a studio in Woodstock, NY.

Presser continued to paint and teach until 1964, when he returned to Europe, to live and paint in Paris, France. He died 3 years later.

The image below is a painting by Josef Presser that we currently have for sale. Click the image to view additional information about the image

If you have a strong inclination to learn more about Josef Presser, visit the Smithsonian’s Archive of American Art. They have part of his personal archive from 1913-1976.

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/josef-presser-papers-8949

Or you can read about some of his work here:

New Deal Art in North Carolina: The Murals, Sculptures, Reliefs, Paintings, Oils, and Frescos and Their Creators By Anita Price Davis

and

Josef Presser 1909-1967 Published by Inter Art Galerie Reich

Santa Fe or Bust!

August 08 2016

Arthur is off to Santa Fe for The Antique Indian Art Show! If you would like to connect with Arthur while he is in Santa Fe, send us an email at: arthur@arthurwerickson.com. We will send you the details of where Arthur will be set up. If you are in Santa Fe, we hope you enjoy all the festivities!

Arthur is off to Santa Fe for The Antique Indian Art Show! If you would like to connect with Arthur while he is in Santa Fe, send us an email at: arthur@arthurwerickson.com. We will send you the details of where Arthur will be set up. If you are in Santa Fe, we hope you enjoy all the festivities!

While Arthur is away the store will continue to be open during regular business hours (Wednesdays: 11am-5pm)

Artist: Norbert Peshlakai

July 20 2016

2 Comments

2 Comments

Norbert Peshlakai (b. 1953; Fort Defiance, Az) is a fourth-generation Navajo silversmith. He was the first generation to gain formal training in jewelrymaking techniques during his 3 1/2 years attended Haskell Junior College in Kansas. From there, Peshlakai returned to his native New Mexico to a life of innovative metalworking.

Peshlakai pioneered new techniques for creating patterns and texture in silver. When He could not find the tool he needed, he would customize tools into specialized instruments, turning concrete masonry nails into handmade stamps and reshaping and grinding hammers to suit his needs. He would also take common items like steel wool to and use them to create texture.

Peshlakai is noted for saying “I like to get a lot of textures going on in the same piece. I like the idea of something looking like it’s beat up all over, sort of bumpy and rough, not a high polished look, but something more unfinished and earthy.”

. Over the years he was won numerous awards, and his work is on display at the Heard Museum in Phoenix.

Welcome Art Collectors and Dealers for the Antique and Collectibles show at the Portland Expo Center

July 13 2016

We would like to welcome everyone to Portland for this weekend's Antiques and Collectibles show at the Portland Expo Center presented by Christine Palmer and Associates.

To learn more about the event please visit their website. Happy treasure Hunting!

Artist: Lee Yazzie

May 27 2016

1 Comment

1 Comment

Lee Yazzie (b. 1946) may have been a bit reluctant to join the jewelry-making scene, but it was simply meant to be.

Lee Yazzie (b. 1946) may have been a bit reluctant to join the jewelry-making scene, but it was simply meant to be.

Both of Lee’s parents, Chee and Elsa Yazzie, were traditional Navajo silversmiths in the “Checkerboard” area of the Navajo Reservation, south of Gallup, New Mexico. They raised 12 children in a one room Hogan. As a child and young man Lee was not encouraged to learn silversmithing. He did not start to learn the trade until he took a silversmithing course at Fort Wingate Boarding School in New Mexico. As his interest was not peaked then, he went on to study accounting at Brigham Young University.

After a year of campus life he realized that his body, due to a congenital hip deformitiy, could not handle the extensive walking. In 1969 he had a surgery on his hip that was not fully successful, during his recuperation he stayed with his mother. He assisted her with her silverwork. Like most, he began with the traditional Navajo jewelry forms of Silver beads and Squash Blossom necklaces. He sold his jewelry to Trader Joe Tanner who instantly saw Lee’s potential.

Tanner encouraged Lee to grow his talents, which lead to a brief apprenticeship with Harold Johnson in Globe, Arizona. There, he learned the art of cutting cabochons, particularly turquoise.

With his new talent in Lapidary, he began working in 1970 at Tanner’s Indian Arts and Crafts Center. He worked until 1975, inlaying stones for well-know silversmiths, like Preston Monongye. By 1979 the interest in his jewelry had grown so much that he worked independently.

In 1980 he designed his first corn bracelet. Lee once said that the bracelet design remind him of when he used to bring in the corn harvest with this brother Benny. The bracelet design did not come to life until 1982 when he took the fuselage like bracelet and inlayed finely honed Royal Blue Lander turquoise in each slot.

Since then, Lee has focused on quality over quantity, becoming a master of metal and stone, producing no more that 10 pieces a year. His pieces feature 14k gold and sterling silver set with lapis, coral, as well as other gemstones that are distinctly modern, but draw from traditional Navajo elements. Perhaps the most used stone in his Jewelry is Turquoise, due to its cultural and spiritual importance to the Navajo people.

Lee was not the only family member to follow in the footsteps of his parent and become a silversmith, the most well known of his siblings are Raymond Yazzie (known for his intricate mosaic inlays) and Mary Marie Yazzie Lincoln. In total, 8 of his 11 siblings are a part of the jewelry-making business.

He and his brother Raymond Yazzie have been known to include upwards of 500 meticulously inlaid stones in one bracelet! And Mary Marie is known for her fine, and very labor intensive, silver beadwork. All three siblings work have included things like necklaces, rings, bracelets, and belt buckles.

Recently, an art exhibit, “Glittering World: Navajo Jewelry of the Yazzie Family”, featured around 300 of the Yazzie family’s jewelry from 1970s to present day. The name of the exhibit is derived from the Navajo creation story. In a interview for the show, Lee spoke of the creation story: “When the Navajos emerged from the lower world to this Navajo earth world that’s what they named it -- the glittering world—and this is the present world that we live in.”

The show held at the has brought together and presented the jewelry as what it truly is—fine art. It is an expression of Native American culture and talent. To watch a short video about the Yazzie family and this exhibit click here.

Glittering World Navajo Jewelry of the Yazzie Family Book can be purchase through Amazon, Smithsonian Store, Barnes and Noble, e

Feature Image is an early Lee Yazzie ring.

Let’s talk…Scrimshaw

May 20 2016

6 Comments

6 Comments

The term “scrimshaw” was coined in 18th Century America aboard a whaling vessel. Its linguistic roots are unknown, but thought to be derived from a Dutch or English or nautical word. The general understanding of the word is “to waste time”. The term scrimshaw also represents more than the carved sperm whale teeth that have become the most recognizable and perhaps most desirable form of scrimshaw, today. All handy crafts (from whale bone corsets busks to carved wood boxes) that were created by sailors on whaling ships in 18th Century America were considered scrimshaw.

The term “scrimshaw” was coined in 18th Century America aboard a whaling vessel. Its linguistic roots are unknown, but thought to be derived from a Dutch or English or nautical word. The general understanding of the word is “to waste time”. The term scrimshaw also represents more than the carved sperm whale teeth that have become the most recognizable and perhaps most desirable form of scrimshaw, today. All handy crafts (from whale bone corsets busks to carved wood boxes) that were created by sailors on whaling ships in 18th Century America were considered scrimshaw.

The most recognized form of scrimshaw is the art of carving images into some form of ivory or bone, in most instances and perhaps most popularly used were sperm whale teeth. Due to the large supply and the lack of commercial value of the teeth, sailors simply had to ask for one, and were not often charged a fee for it. The teeth then had to be smoothed of all ridges and imperfections prior to carving. The first layer of imperfections was almost always scraped away with a knife, and then the scrimshanders would use sharkskin or pumice to smooth the surface further. Finally, the teeth would be buffed with a soft cloth to achieve a high glossy finish.

The tool of choice was a needle, but if the sailor could not lay his hands on one, his trusty pocketknife would do the trick. Using his tools the sailor would scratch and/or carve an image into the polished tooth. As the image began to take shape the sailor would rub pigment into the already cut/etched surface, revealing his design. Since ink was not easy to come by, sailors would use things like soot or ground gunpowder mixed with whale oil to create pigment. General themes included sweethearts from home as well as life at sea, like whaling ships dashing across the waves or Mermaids sunbathing on rocks.

It is important to note that the term or technique has grown to include Eskimo Ivory carvings. There are Eskimo ivory carving that pre and post-date the whaleman’s scrimshaw, which may indicate simultaneous development this art form. It is also hypothesized that the Eskimos borrowed this style of art from Russian traders that were in eastern Siberia as early as the 17th century (Ray, 99). The theory is that the Russians were trading with the Native Alaskans even before the first explorers made it to Alaska’s coasts. However, nothing as graphically-advanced as the whaleman scrimshander’s art would be seen from the Eskimos until after 1835 when the first Whaleman traveled to the islands of Alaska.

Through creative exchange the Whalemen received access to new materials, like mammoth and walrus tusks as well as a revived cultural interested in scrimshaw art. The Eskimos gained new ideas of items, like cribbage boards, pipes, cane handles, and napkin rings, to be created for commercial sale. It was a win-win situation.

One of the most well known Eskimo carvers is Happy Jack, originally named Angokwazhuk. He hailed from Diomede Island and was convinced to accompany Captain Hartson Bodfish on a journey to San Francisco in 1892. During this journey he acquired the new name as well as “new ideas that added to his own talent in ivory carving.” (Flayderman, 247). Through his and other Eskimo carvers success and the increase in visitors to Alaska during the Alaskan Gold Rush there was a surge in the collection of Scrimshaw and Eskimo carving which made it an important part of the Eskimos’ livelihood.

As whaling faded so did the scrimshaw trade by the turn of the 19th century most sailors had moved on to other jobs and life in general had changed. However, in the 1960’s President John F. Kennedy’s collection created a revival in the creation and collection of this unique art. This revived interested has continued and evolved due to restrictions on the buying and selling of ivory. To learn more about scrimshaw we suggest looking at our resources as well as the New Bedford Whaling Museum site.

New Bedford Whaling Museum, located in Bedford, Massachusetts, has a Scrimshaw Weekend every year dedicated to “the indigenous shipboard art of whalers during the ‘Age of Sail.’” It has several events through out the weekend that you can choose to attend or purchase a weekend pass for all the festivities.

Resources for this blog include:

A Legacy of Artic Art by Dorothy Jean Ray

Scrimshaw and Scrimshanders Whales and Whalemen by E. Norman Flayderman

“This History of Scrimshaw” from Hops Scrimshaw http://www.hopscrimshaw.com/about/scrimhistory.htm

The images used in this article are items that are currently for sale on our website. To see more scrimshaw items please visit our Eskimo collection

Sharing a piece of history, remembering Gilbert D. Schneider

May 12 2016

We recently received part of Gilbert D. Schneider's African Tribal Arts collection. With permission, we are sharing with you his obituary written by Christraud M. Geary, for Tribal Arts Spring 2000 issue. Full citation below image.

Spring 2000, Vol. 33, No. 1, Pages 17-17

Spring 2000, Vol. 33, No. 1, Pages 17-17In Memorian: Gilbert D. Schneider, 1920-1999

Christraud M. Geary

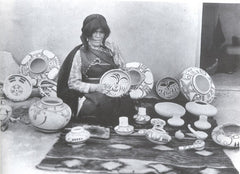

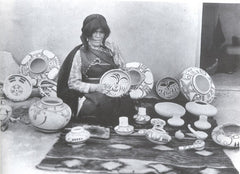

Nampeyo: Tips for Identifying Her Designs

May 06 2016

Are you ready for another long post? We had some technical issues and a few busy weeks that put this blog behind, but I think we are back on track.

Are you ready for another long post? We had some technical issues and a few busy weeks that put this blog behind, but I think we are back on track.

Nampeyo had five recognizable periods of pottery. We hope to share with you tips on how to recognize the pottery that will not only help you identify a Nampeyo pot, but also roughly when it may have been made.

A few general notes to start:

- Nampeyo was known to use two colors of clay. The first being gray that fired to a warm cream to honey color and the second being yellow that fired to be a burnt orange-brick red color.

- She was not always meticulous in the smoothing of the interior of her pots and would sometimes leave the bottom of the pots unpolished.

- She would sometimes add a color slip of red, yellow, or white over gray clay.

- Most pots that are signed with Nampeyo’s name are signed by one of her daughters or relatives, because Nampeyo did not write.

- Early on, Nampeyo’s daughter Annie made pottery alongside her mother. This is important to note, because during the earlier periods of Hopi pottery the bowls, pots and other vessels were left unsigned, which in turn allowed many pieces of pottery made by Annie to be misattributed to Nampeyo. Annie’s pottery has some distinct characteristics. She often created black or black-and-white designs on a red slipped surfaced pots and her earlier pieces often used large black elements with scant amounts of line work. The shape of Annie’s pottery also varied from her mother’s in that it was shallower and more angular.

- Annie was the first to paint repeated migration designs, easily identified by her signature dots fount at the end of the “wingtips”

- It is also important to mention Nampeyo marriage to Lesso of the Cedarwood Clan of Walpi; He is often noted to have assisted her in the copying of ancient designs or assisting her in the painting of pottery after she began to lose her sight to trachoma. Currently there is no photographic record of designs he created.

- Nampeyo used similar designs between the exteriors of her pots and the interior design of her bowls. There was more freedom to play and improvise with linear shapes, repeating patterns, and abstract designs in the bowls because of the flatness of the interior.

- Many Nampeyo pieces feature a “roadline” that can be found just below the rim of her vessel

- It is rare to see a painted rim on Nampeyo pottery. However she was experimental, so it is not out of the question. Due to her enjoyment for improvisation in her design there are likely to be several unattributed pieces floating about of her more creative work.

Period 1 is recognized as all of Nampeyo’s work before 1900. Her inspiration as a young woman stemmed from the pottery and shards found in surrounding Hopi territories and the Antelope mesa that had been abandoned due to violence from outside tribes or just simply abandoned for better locations. What started as mimicking of past designs, bloomed into a beautiful creativity and a keen eye for balance of design and shape.

During this period major design themes emerged, included Kachina faces, curvilinear designs and bold frames. She painted these design on U-shaped bowls, bowls with spherical sides and inverted rims as well as bowls with an inwardly rolled rim. Are you noticing a theme? The bowl shape allowed for more creativity in painted designs and is a good beginner’s shape when learning coil pottery.

Period 2 is when thing really began to pick up. Between 1900 and 1910 Nampeyo was her most improvised and diversified in shape and design of pottery. Her shapes often included large globose vessels. These vessels were often included in photographs of Nampeyo during this time because of their impressive nature, however they were not part of her typical output.

Her signature vessel during period 2 would be the Sikyatki shaped jars that are 18 to 20 inches in diameter, with a low profile and truncated neck. She also began to form seed jars that would be a main stay in her creative career.

The eagle tail design was prominent during this time, especially on the Sikyatki shaped jars. She varied this design through the use of different colors, as well as varying the linear design above the extended “feathers” which also varied in quantity and size. She began to use the “wingtip” design from the migration design in numerous variations during this period. Although Nampeyo was a fan of the “wingtip” design she rarely use the migration pattern, which it is derived from, in its entirety.

Many designs from this period would carryover to future periods, but others like the “spider” design would be isolated to Period 2.

Period 3 was short and fast. From 1910 to 1917 the high demand for tourist pieces caused all Hopi potters to kick up production early during this period. However there was a steep decline in visitors due to the start of World War I. Demand for pottery plummeted.

Shapes that are prominent during this time were medium-sized vessels with more flatly rounded bottoms and sidewalls that had a more gradual angle from the base. The shoulders of the pots were slightly concave and then tapered to the opening. This style pot was easier to transport. Nampeyo also continued to create seed jars of sizes. Along with new shapes come new designs. During period 3 is the first record of the “batwing” design, which was featured on seed jars, large and small. From 1912 to 1915 a circular motif pops up in many of Nampeyo’s pieces. This motif was often alternated with the A-shaped stylized Kachina face.

Period 4 (1917to1930) was rough on Nampeyo. Her eyesight began to decline in earnest. However she took it in stride and continued to do what she loved. During this time there is a lot of experimentation with shape and tactile design. Keep your eyes out for corrugated necks on Hopi pottery because it may point to the pot as being one of Nampeyo’s. She began to use this texture in the early 1920s. She also created figurines necessitated by the demands and request of tourists.

Designs during this period varied and were not often created by Nampeyo. Her failing eyesight forced her to allow others to paint many of her pots. However to know who painted which pots would require much more study of the Nampeyo pots collected from period 4.

Period 5 began with the loss of Nampeyo’s husband, Lesso, in 1930 and closed with Nampeyo’s death in 1942.

After Lesso’s death, Nampeyo with drew from her work for a period of time only creating a few pieces at a time, and entering even fewer into the Northern Arizona Hopi Craftsman Exhibit. By the mid 1930s her family began to help her gather her supplies, allowing her to shape vessels more frequently. She continued to shape vessels until 1939. Many, if not all, vessels shaped in during this period were painted by one of her family members, including Annie, Fannie, Daisy, or Lena Charlie. You may find that the vessels from this period have two name inscribed on the bottom, Nampeyo and the family member -painter’s.

Featured photography by A. C. Vroman, Hano, Arizona; 1901.

Nampeyo, The Potter's Process

April 13 2016

Nampeyo’s, like many other native Tewa-Hopi Natives, process began with the collecting of clay. Then the slow process of smoothing the clay would begin, squishing the clay with her feet, Nampeyo would remove small pebbles and other debris. Once all of the larger pebbles were removed the clay would be placed on a kneading stone to be further smoothed. Often Nampeyo would add sandstone dust to created an even smoother texture to the clay.

Nampeyo’s, like many other native Tewa-Hopi Natives, process began with the collecting of clay. Then the slow process of smoothing the clay would begin, squishing the clay with her feet, Nampeyo would remove small pebbles and other debris. Once all of the larger pebbles were removed the clay would be placed on a kneading stone to be further smoothed. Often Nampeyo would add sandstone dust to created an even smoother texture to the clay.

Then the no less strenuous task of coiling the pots or bowls began. After every second or third coil of clay, Nampeyo would use a melon or squash rind to smooth the surface of the quickly forming pot. Using her best judgment, Nampeyo would pause in the construction of the pot if she felt the wall of the pot could no longer bear the weight of additional coils of clay, leaving it to dry, thus strengthening the walls to allow her to continue with the process at a later time.

After the coiling and smoothing process was complete Nampeyo would use mineral colors ground on a natural slab, creating shades of red, white, and dark brown. To create black she would use beeweed or mustard plant, boiling it down to a syrup and allowing it to dry on cornhusk, the ancient version of saran wrap. Allowing the cakes of pigment to be easily peeled off and then chunked for storage or dissolved in water to create a smooth paint. Of course every painter needs her brush. Nampeyo use the traditional yucca switch that had been mashed allowing the fibers to separate. For less detailed work or large areas of her designs swabs of wool from a local sheep worked just fine.

Are you tired yet? Well Nampeyo’s work wasn’t done. While the painted pottery dried, she began to build a base of sheep's dung under a grate in the center of a circular ring of sand. Then after the pottery was thoroughly dry and warmed through it would be place on the grate and surrounded by pieces of broken pottery. These remnants of failed pieces were used to protect the new pottery from the fire. More sheep’s dung had to be layered on to create a dome and then left to burn for several hours.

Like in modern pottery techniques Nampeyo added unique items, like sheep bones, to be burned during the firing process to alter the final look of her pottery. Although it is not recorded that she explain her reasons for adding the bones, one theory is that it would make the pottery whiter.

Reflecting on the dedication that Nampeyo showed to her craft with each step, from the collection of clay to the thrill of holding a finished piece, no one can doubt that Nampeyo worked hard. Pottery was not only her livelihood for many years, but also a life long passion.

Featured image by Adam Clark Vroman, Nampeyo building a wall of fuel, 1901, Smithsonian Institution [Public domain]

Artist: Nampeyo (Num-pa-yu, translates to: snake that does not bite)

April 07 2016

Most people who collect Hopi Pottery have heard the name: Nampeyo. This week we will talk about her life and in the weeks to follow we will talk more about her inspiration, technique and design aesthetic.

Most people who collect Hopi Pottery have heard the name: Nampeyo. This week we will talk about her life and in the weeks to follow we will talk more about her inspiration, technique and design aesthetic.

Nampeyo, born around 1860, had a very traditional upbringing as a member of the Corn clan of the Tewa-Hopi tribe. As a child in the Tewa-Hopi community she would have been involved in all the day to day activates: collection of corn, gathering of water, cooking, and some sort of artisan work. In Nampeyo’s case it was the craft of pottery. In her youth, she began learning her craft from her mother, White Corn (although many sources state that she learned from her paternal Grandmother). She was taunted with the name “old lady” because she showed so much interest in the craft. Of course, when her talent for pottery became more apparent, this taunt became a term of endearment to those who knew her.

Her talent did not go unnoticed by outsiders. Her brother, Tom Polacca, was a tribal leader and interpreter. His line of work drew attention to the family, and more so Nampeyo. She was a young and attractive Native woman, who was very talented. Nampeyo and her craft were documented by well-known photographers like William Henry Jackson, Adam Clark Vroman, and Edward S. Curtis over the span of her 82-year life.

Nampeyo’s creativity continued through the prime of Hopi-Tewa pottery in the 1880s. Ethnographers and Anthropologists from all over the United States took notice of the Hopi-Tewa culture. Due to the isolation of the tribes-people, they were able to maintain their traditional lifestyle and cultural ceremonies. During this time tens of thousands of items were collected, and not the least of which was pottery. Nampeyo’s pottery was collected along with every other Hopi/Tewa woman potter, with little recognition. However from 1890-1900, she was one of two women potters register as still pursuing the craft as a career.

From 1890 to 1910, Nampeyo’s reputation grew and she quickly became one of the most a sought after Hopi potters. Nampeyo was invited to opening events and exhibts like the Hopi House opening, New Year’s Day 1905. She and her family stayed as Artists in resident for three months providing a bit of Native culture to the themed hotel. In the following years, she would make a second trip to the Hopi house, to yet again to be on display, creating her art. Nampeyo was later invited to Chicago for the 1910 United States Land and Irrigation Exposition to demonstrate her skills along side modern machinery.

However, as she aged trips like this appealed less and less. She might have been termed a homebody, but she had her family and friends that would come to enjoy her hospitality and excellent story telling, especially, the artists who came to Polacca to soak in the culture, like E. Irving Couse and his wife, Virginia, and Carl Oscar Borg.

During the rise and fall of the fad of owning Hopi material culture, Nampeyo became a shrewd businesswoman, knowing when to make additional pottery in preparation for the peak of the tourist season, during the Snake Dance ceremonies. She also knew her value as an artist, not allowing outsiders to dictate her prices. She was a cheerleader for her craft and invigorated the art of pottery in her community of Hano, First Mesa, Arizona until her death in 1942.

For further study, we recommend Nampeyo and Her Pottery by Barbara Kramer. Barbara Kramer includes an extensive Bibliography and was a source for this blog post.

Featured image: By Charles M. Wood, 1908-1910 [Public domain]

Store Happenings

March 30 2016

Hello Readers,

We hope you were all able to make it to the store today. If not, feel free to contact us with any questions you may have. Arthur will not be available for appointment or in store until April 20th. The store will be open Wednesday April 6 and Wednesday, April 13th, as usual. Rachel, Arthur's assistant, will be there and happy to track down answers to any questions you may have. Please come and say hello!

Also, keep your eyes peeled for this week's blog post on Nampeyo, the Hopi Potter.

Arthur Erickson and Team

Let's Talk...Imbricated Baskets

March 23 2016

The first thing to note is that imbricated baskets in North America are unique to the lower Pacific Northwest and Cascades-Plateau regions, most notably from tribes like the Klickitat, Cowlitz, and Salish.

Imbrication is considered a decorative overlay technique that is seen on coiled baskets. Decorative organic materials, like strands of bear grass, horsetail root or the inner bark of the chokecherry plant, are caught under select stiches, binding the added material to the exterior surface of the basket. The weaver would then fold the decorative strand regularly back and forth on itself to create patterns on the outer surface of the basket. These imbricated patterns feature geometric designs or cultural motifs and would cover part or all, of the Basket’s surface.

Other notable things when looking for Imbricated baskets include that decorative materials were either left their natural color or dyed in tones of red, yellow, black or white, as well as the fact that the designs are not visible on the interior of the basket. The surface texture of an imbricated basket has been likened to rows of corn kernels or roof tiles.

Most Native arts are a tactile experience and imbricated baskets are a prime example of this. To see more examples of Imbricated baskets on our site, visit our American Indian Basket Collection.

If you wish to learn more about the tribes that made imbricated baskets we suggest picking up a copy of Indian Baskets by Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh and William A. Turnbaugh

Artist: Mark Chee

March 16 2016

We recently posted a Mark Chee belt buckle, but what do we know about him…? Like many other Native Americans, he attended a boarding school: Fort Defiance boarding school, to be exact. He began school at the age of 10 and completed his education in 11th grade.

We recently posted a Mark Chee belt buckle, but what do we know about him…? Like many other Native Americans, he attended a boarding school: Fort Defiance boarding school, to be exact. He began school at the age of 10 and completed his education in 11th grade.

Shortly there after, he arrived in Santa Fe eager to work, and work he did. Chee polished stones for $5.00 a week. One can suppose that he began to hone his stone working skills here. He moved on to be a benchsmith for well-known silversmiths, Frank Patania and Al Packard.

He produced most of his art from 1930 to the late 1960s; each piece carries his hallmark of a stamped bird containing his last name. He was became an important silversmith for the Mid-20th century and is well know and highly collected.

His jewelry is characterized by the use of heavy silver, stampwork, and set stones. Later in his career he branched out into crafting beautiful sets of flatware.

Trying Something New

March 09 2016

Hello Readers,

Welcome to our blog! We have decided to try something new, so bare with us as we explore Native art and learn more about the artists who make it. Once a week, we will feature a type of Native art or artist that we have in the store and online. These quick and enjoyable reads will help you learn more about the art you are collecting and we hope, will spark your interest to learn more about Native art.

This blog will also have updates on art events we attend, as well as what shows we will be participating in. We enjoy hearing feedback from our customers and having an open dialogue about Native art.

In the future we may branch out to feature other types of art, making our blog as eclectic as our store. Please enjoy!

Sincerely,

Arthur Erickson and Team

A Satisfying Trip

February 24 2016

Arthur has made it back from the San Francisco Tribal and Textile Arts Show. Come see all the great things that he found there!